Emmylou Harris, in the voice of an angel, recounted a tale so horrific that it would make the devil himself feel shame.

I was born a black boy

My name is Emmett Till

Walked this earth for 14 years

One night I was killed

For speaking to a woman

Whose skin was white as dough

That’s a sin in Mississippi

But how was I to know?

At least I believe those were the words she was singing. I could only make out every second or third word, at best, because the people in the row behind me at the Mann Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia were talking and laughing loudly throughout the song. Just as they had since they arrived midway through the opening set by Carlene Carter (3rd generation member of the legendary Carter Family and daughter of June Carter Cash, who collaborated with the night’s headliner, John Mellencamp, on his latest album, Sad Clowns and Hillbillies).

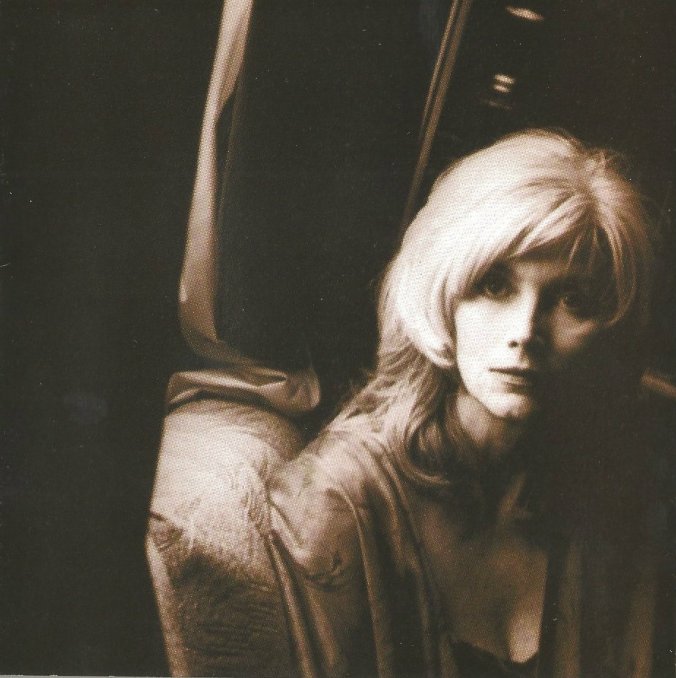

And just as they continued to do for the entire set by Emmylou, a Country Music Hall of Fame artist who has graced several of the finest albums of the past 40-plus years with one of the most gorgeous voices on the planet, moving seamlessly between country, folk, rock, and other genres.

Now 70, she is a beautiful thread that weaves together Gram Parsons, Bob Dylan, John Prine, Willie Nelson, Mark Knopfler, Conor Oberst, Neil Young, Rodney Crowell and so many others … not to mention her Trio collaborations with Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt. And she has written songs of uncommon poignancy that stir the souls of those willing to listen.

Mansfield Frazier is one such soul. Five years ago, the former Cleveland newspaper editor wrote a piece for the Daily Beast that expresses the profound effect hearing Emmylou Harris sing “My Name is Emmett Till” on the radio had on him. Frazier was 12 years old in 1955 when details of the unspeakable torture inflicted on the 14-year-old Till for the “sin” of flirting with a white woman in Mississippi made national news, one of the sparks that lit the Civil Rights Movement.

Frazier, who is African-American, writes:

“But 56 years later, I listened, transfixed, as Emmylou Harris sang her version of the story with heartbreaking tenderness, and I was awestruck that a 65-year-old white woman, born and bred in Alabama, would have the compassion and the courage to perform this song in front of a country-and-western audience—in Nashville no less. Her sincere voice and remarkable words evoked such long-ago memories that I could feel a huge lump in my throat.”

I urge you to read Frazier’s heart-rending, yet ultimately hopeful, column. It is proof that, for those with ears to listen and a soul to understand, music has the power to confront hate and awaken “the better angels of our nature.”

But that only happens if you listen. And increasingly, I have found that fewer people are listening to artists at larger venues. Perhaps I was just unfortunate enough to be in the wrong row at the Mann, with the lone group of loud-mouthed, self-absorbed jerks directly behind me. But from the loud buzz I could hear even when the idiots behind me were momentarily quiet to take a breath or gulp a beer, I doubt it.

‘A few soft words in pursuit of quietude is no vice’

In talking with music-loving friends, I’ve heard plenty of similar discouraging stories. It’s reached the point where that bastion of good manners and taste, NPR, recently felt compelled to address the musical question: Can I Ask Loud Talkers At Outdoor Concerts To (Please) Shut Up?

Personally, I don’t even consider that a question. Being NPR, of course, their answer is more refined and thoughtful. Stephen Thompson writes in his column, The Good Listener:

“As for what to say and how to say it, be polite and friendly, stick to “I” statements as much as possible (“I’m having trouble hearing the show…”), and try to be as brief and direct as possible. Speaking a few soft words in pursuit of quietude is no vice.”

Well, yes, you could do that. It’s certainly an impeccably reasonable way to approach the situation.

‘I hope the music isn’t interfering with your conversations and phone calls!’

But I must confess I took a decidedly different tack when Bruce Springsteen and the E-Street Band played the first concerts at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia back in 2003. I was sitting in the second row of the upper deck with my wife, and in the row directly in front of us was a younger group that had obviously been tailgating in the parking lot for some time before the show began.

When the show started, they hardly seemed to notice. They continued yelling back and forth, up and down the row, and talking loudly on their cell phones. I finally lost it when Bruce went into a fierce, full band version of “Lost in the Flood” from his first album. When the song ended, I reached down and grabbed the two guys in front of me roughly by the shoulders, leaned forward between them, and, with what I’m sure was the full Jack-Nicholson-in-The Shining crazy in my eyes, said: “I hope the music isn’t interfering with your conversations and phone calls!”

In my defense, I did use an “I” statement. Although I’m pretty sure that’s not quite what The Good Listener had in mind.

Stunned, they stared at me like I was a lunatic (which was probably a fair assessment) and then started stammering about how they loved Bruce and were listening and hadn’t spent the entire show talking to each other and on their phones. That was when I noticed that virtually the entire row in front of me really was all one group. Once they got over the initial shock, they all turned around and started shouting at me that I was trying to spoil their fun because I was old and it was my problem, not theirs. Besides, they said, nobody else was complaining.

It felt like it was about to get uglier fast, when an amazing thing happened. The people next to my long-suffering wife and I and the folks in the row behind us—all strangers in the City of Brotherly Love—started yelling back at the front row that they had, indeed, been acting like jackasses and ruining the show for them. With the numbers suddenly on my side, the front row sulked back in their seats, and were noticeably less obnoxious the rest of the show.

Later, the most drunk guy in the group looked over at me, glassy eyed, and said: “I hope I’m never as old as you.” I smiled, and replied: “I hope you never are, too.” He looked confused as to why I was agreeing with him. I doubt it ever penetrated the fog.

I’m not proud of the way I handled the situation, and don’t recommend this approach to others. There have been several times since when I’ve had to ask people to pipe down, but I’ve managed not to do it in such an aggressive, confrontational manner.

‘The fault is not in our stars …’

I have several friends who love music, but have given up on going to concerts at larger venues because of the routine rudeness they so often had to deal with. I know even more people who have given up going to movie theaters for the same reason.

I understand their decision, but chafe at the idea that people who are really passionate about the music should be the ones to stay home. Especially since, unlike most of the real problems facing the world, the answer is simple: If you have no interest in hearing the opening acts, stay out of the venue until the headliner shows up. And if you have no interest in actually listening to the headliner, then save yourself a ton of money and don’t go to the show.

Of all the things that divide us as a people these days, I must admit the one I find most mystifying is that there are actually people who think nothing of spending upwards of $100, plus shelling out for a half dozen or more $10 beers or even more expensive cocktails, to go to a concert and not listen to the music. It’s like they’re at their local bar, and the performers are the jukebox (or nowadays, Sirius or Pandora) playing in the background as they regale their friends with tales of work and the absolutely fascinating things that have happened in their lives that week.

When I see these people at shows, talking loudly to one another or on their cell phones, paying little or no attention to the stars on the stage, I can’t help but think of the words of one of Emmylou’s former singing partners, the Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan: “It’s a wonder that you still know how to breathe.”

You hear a lot of complaints about stars who go through the motions, failing to perform with the passion and energy and artistry expected. That certainly hasn’t been the case at most of the hundreds of shows I’ve seen. And from what I could tell, Carlene Carter, Emmylou Harris, and John Mellencamp were at their best in Philly, delivering passionate performances and engaging (or at least trying to) with the audience. Dan DeLuca’s review in the Philadelphia Inquirer certainly confirms that.

For me, it’s a simple matter of respect—for the performers and for the music. Buying a ticket doesn’t entitle you to be a jackass.

I’m also reminded of a line by another pretty fair writer, William Shakespeare: “The fault … is not in our stars, but in ourselves …”

Coda: My Soul’s Got Wings

Emmylou Harris and Carlene Carter join John Mellencamp and his band for a spirited version of “My Soul’s Got Wings” at the Mann Music Center In Philadelphia on July 6, 2017.